First scientific post.

Here we go.

Next week will be fun. My friend and I will climb Mount Rainier. At 14,411 feet (come on USA, who still measures in feet!!!), I mean, at 4,393meters, it will give us a short experience of high altitude.

It will be also a great opportunity to bring my new baby on the trail, my portable ultrasound (Vscan with Dual probe, GE).

The goal is to scan our lungs at sea level (Montreal, Canada), Paradise (start @ 1,646m), Camp Muir (3,105 m) and hopefully the summit.

Literature already exists on lung ultrasound at high altitude.

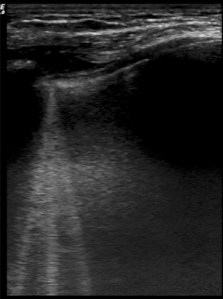

The main findings are the comet tails. They are described as hyperechoic, with a narrow start from the pleuritic line, extending deeply in the lungs. It has been extensively studied for cardiogenic pulmonary edema and it is a sign of fluid accumulation in the lungs.

This is a good example of comet tails:

(Source : Wimalasena et al, Wilderness Environ Med)

In a study done in high altitude, all of the subjects (18 out of 18) had ultrasound lung comets (ULCs) at 4790m. None of them had comet tails at baseline (1350 m). The higher they climbed, they had more comet tails. For their study, ultrasound lung comets were evaluated on anterior chest at 28 predefined scanning sites. They summed up all the comet tails they saw into a score.

In the group, three patients had clinical High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE) and all had ULCs. Table 2 of this paper shows impressive data. After being treated, the blood pressure and oxygen saturation of patients with HAPE improved. What is more striking is that the number of ULCs decreased in subjects with HAPE after treatment.

Here is another paper on the subject. It is a review article without any mention of the methodology they used to find article. In sum, an inverse relationship exists between the number of ULCs and oxygen saturation. Also, a higher ULCs count is correlated with a higher Lake Louise Score. (The Lake Louise Score is a useful tool to diagnose acute mountain sickness (AMS), a totally different entity from HAPE. Still, AMS is a frequent comorbidity when HAPE is present. But let’s stay focus on HAPE). In two studies they identified, when patients were treated for HAPE, the ULCs count decreased and O2 saturation increased.

——————

In short, ULCs are sensitive but poorly specific. If you are high and evaluating a patient with shortness of breath who has no comet tails, think of something else than HAPE. But if the patient has ULCs, it doesn’t mean the patient has HAPE because a lot of asymptomatic patients will have comet tails.

I am totally in love with my ultrasound machine. But for lung ultrasound in high altitude, as of now, it wouldn’t change my management.

To date, there are far more questions than answers on this subject :

- How should we monitor ULCs when climbing?

- Is there a threshold number of ULCs for the diagnosis of HAPE?

- Should a standardized approach be developed for lung ultrasound?

- Should we monitor the decrease in ULCs when treating someone with HAPE?

- ULCs are good to identify subclinical HAPE but what does « sublinical HAPE »mean anyway?

- How does ULCs evolve with acclimatization?

——————

Next post will be our lung ultrasound pictures from Rainier.

——————

References :